- cross-posted to:

- technologie@jlai.lu

- cross-posted to:

- technologie@jlai.lu

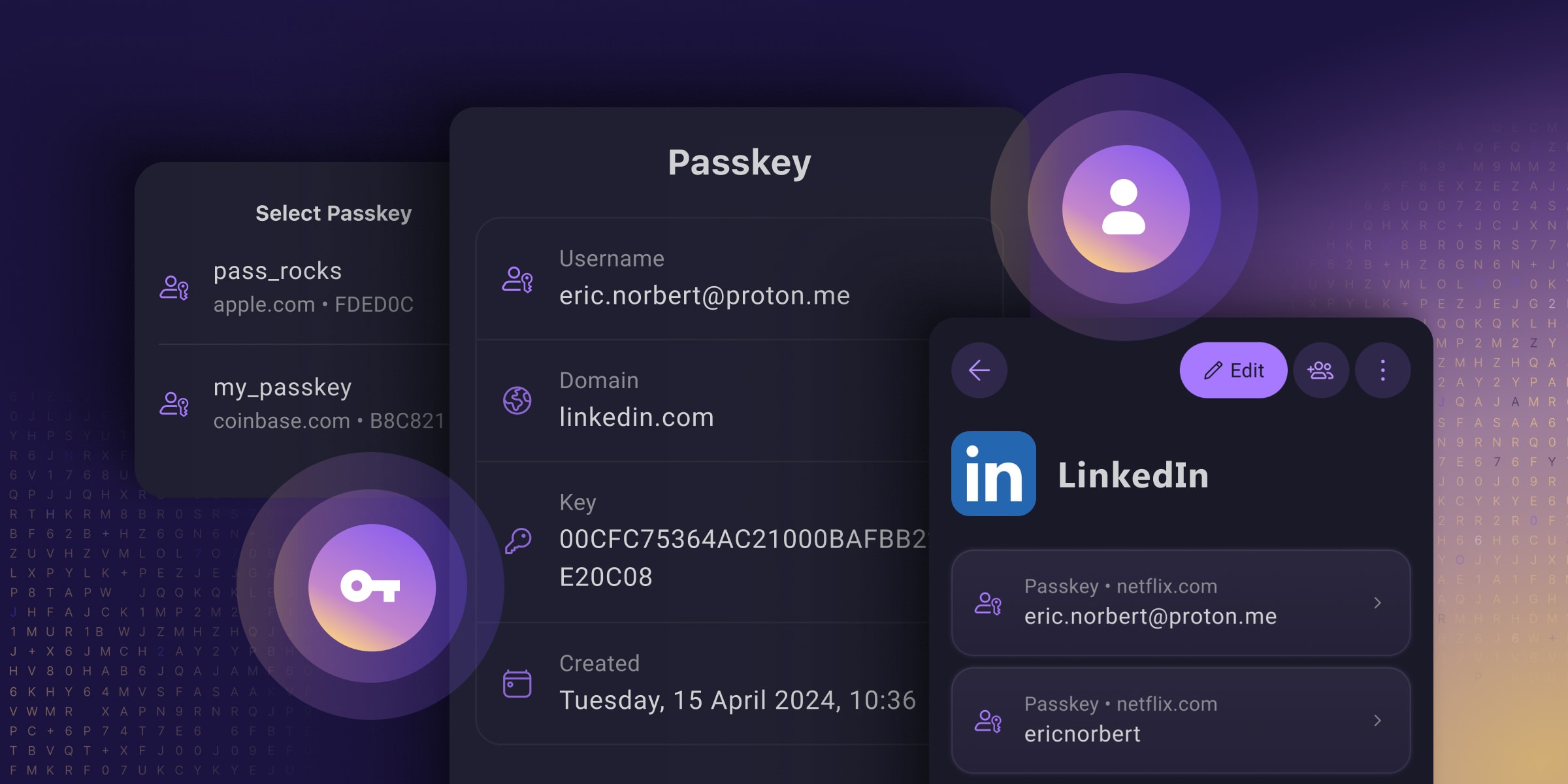

Passkeys are an easy and secure alternative to traditional passwords that can help prevent phishing attacks and make your online experience smoother and safer.

Unfortunately, Big Tech’s rollout of this technology prioritized using passkeys to lock people into their walled gardens over providing universal security for everyone (you have to use their platform, which often does not work across all platforms). And many password managers only support passkeys on specific platforms or provide them with paid plans, meaning you only get to reap passkeys’ security benefits if you can afford them.

They’ve reimagined passkeys, helping them reach their full potential as free, universal, and open-source tech. They have made online privacy and security accessible to everyone, regardless of what device you use or your ability to pay.

I’m still a paying customer of Bitwarden as Proton Pass was up to now still not doing everything, but this may make me re-evaluate using Proton Pass as I’m also a paying customer of Proton Pass. It certainly looks like Proton Pass is advancing at quite a pace, and Proton has already built up a good reputation for private e-mail and an excellent VPN client.

Proton is also the ONLY passkey provider that I’ve seen allowing you to store, share, and export passkeys just like you can with passwords!

See https://proton.me/blog/proton-pass-passkeys

#technology #passkeys #security #ProtonPass #opensource

Are sufficiently long passwords susceptible to brute force attacks?

Don’t passkeys get that feature by just being longer?

Yes. Thought obviously the odds of success go down the longer and more complex that password.

Put simply… no. Passkeys aren’t just ”longer passwords” sent to the same place. Unlike passwords, Passkeys aren’t a “shared secret” that you’re sending to the service you’re authenticating to. Passkeys use asymmetric encryption and are neither sent to nor stored on the server you’re authenticating to. Your passkey is a private key stored on your device and secured by biometrics, the paired public key for which lives on the server you created the passkey to authenticate to.

In a traditional brute force operation, you’re sending guesses to a server that knows your password. If you send the correct guess, you get in. It’s also possible to steal the password from the server and brute force that offline.

With a passkey on the other hand, the server uses your public key to encrypt a string in a challenge message, this string can only be decrypted by your passkey. You then send a response that’s encrypted by your private key, which can then only be decrypted by the public key on the server. So the thing you’re sending to the server to authenticate isn’t your passkey, and it’s unique every time you log in.

So could you perform some kind of operation that would technically still be a kind of brute force? Theoretically yeah. But even so you’d be limited to brute forcing against the server, which isn’t very effective even against passwords. However you would not at all be susceptible to offline brute forcing based on the capture of a passkey either in flight by breaking encryption, or by breaching the server, because your passkey never leaves your device.

Thank you, that was a really helpful explanation that I haven’t seen elsewhere. It helps a lot and I think I now understand the difference between passwords and passkeys.

I still don’t like the hassle inherent in passkeys, but at least I understand it now.

Oh yeah no problem. The internet is flooded with high level answers that don’t really explain it in any detail.

I wonder what hassle you’re having? Passkeys should be much less hassle than passwords.

The hassle is that I have to have a second device to login with, and I have to keep that device with me and functioning at all times.

Obvious answer is of course my phone, but I’ve had a few situations where I needed to access an account on a new system and didn’t have a 2nd device available.