I guess I should post my comics here, rather than DnDMemes :)

Can I retitle this to

Creative Character concepts I wish my players would come up with.

Character concepts I HAVE played in recent years:

Goblin priestess of Tymora who’s on a mission to free her people from their tyrant god Maglubiyet, and change hearts and minds for goblins in large cities through setting a personal good example.

Treant druid who’s on the run from the authorities because she keeps planting knotweed in the foundations of various large buildings and temples. (I used the tortle lineage for stats)

Middle sibling from a noble family who is competing against all the other siblings to “earn the most money” by a set date, because the one who brings the most cash home gets the family inheritance. Decided “adventuring” had the best return for time spent.

Imprisoned Artificer who designed and built a robot (5e “nimblewright”) that she could telepathically pilot - then sent it out to go recruit an adventuring party to rescue herself.

I love the art. It’s adorable.

From the character concepts my favorite is the noble competing for gold and treasure. It’s a fun twist on the I’m here for the money motivation.

The construct trying to save the master is cool as it can potentially lead to swapping characters after a while. But it’s a bit main charactery for some campaigns.

It did lead to swapping characters, at level 6! I went from Warforged Artificer to Gnome “Inventor” (she’s a wizard, but I reskin all of the spells as tinkered inventions)

(These two tokens are what I used for the nimblewright)

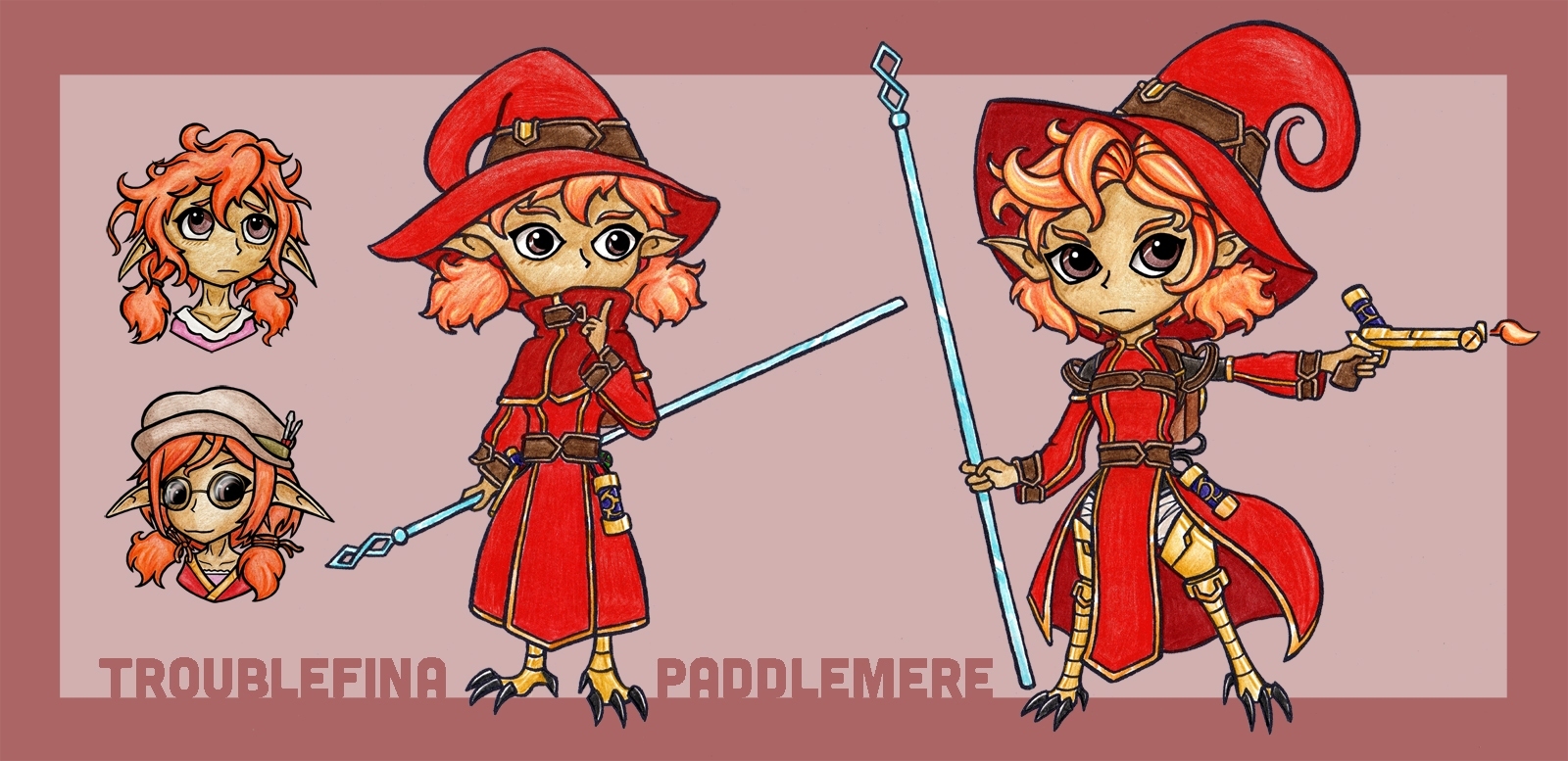

(This is the key art for the gnome inventor)

As for the “main character-y” stuff… I basically hid the entire backstory from the group for 6 months of play, my character was worried that agents of her captors might track her down and put an end to her one shot at a rescue, and since their an organization with active spies all over the place, she was hiding everything until she was sure she could trust the group.

Over time, I told different characters part of the story, in confidence, which lead to (at one point) every other PC in the group having a completely contrasting explanation of what my “deal” was, under instructions to not tell anyone else.

Once I actually came clean and explained the situation to them, they organized a rescue op and saved her in 3 sessions. Less of a “main character” result and more of a “character side-plot” outcome - everyone else has their own personal side stories, and some of them are pretty involved…

Your group is different from ours. Literally all of these would be “yes! What else about this character is strange or interesting”

And we’ve never had a wizard who wasn’t a walking catastrophe. Or a warrior. Or a bard. Mostly the bards. The bards are all disasters

Ah… my “groups” - most of these have been vetoed by different DMs for various sensible reasons.

What were the reasons?

Usually just that it was a bad fit for the campaign tone. In the case of “wizards” it was “not after what you did last time” :p

I really like the warforged druid concept. Very beast wars to me lol

And if you take 3 levels of armorer you can have your armor change to fit your new form to have a good AC and shoot lightning as you slither around as a robosnake

I’ll probably post some of my more popular comics to support this project, but… maybe only a couple a week so as to not flood the place :D

My last game, I ran a Swashbuckler Rogue/Vengeance Paladin who took the Defensive Duelist feat. His primary character motivation was to get revenge on the man who killed his fa-

Fuck it, let’s dispense with the pretense, it’s Inigo Montoya. I played Inigo Montoya.

Ok but the warforged druid one is genuinely pretty awesome.

Any particular stories on why you’re banned from playing wizards?

I tend to have a habit of looking at all the tools I have, and using them to the greatest possible effect I can…

I played “Princes of the Apocalypse” with a Pyrophobic Librarian called Neff, who refused to take most evocation spells - the entire table accused me of sandbagging by refusing to take fireball…

Let me tell you, half the bosses in the campaign were unable to act, because every spell they cast was counterspelled by a tiny gnome with spell slots not being reserved for DPS. The other half of the bosses suffered from being extraplanar entities hit by the banish spell with a 100% guaranteed success rate. My DM refuses to let anyone play diviner ever again.

Let’s see what this terror of the module looks like.

The worst trick I sat on, and I saved it entirely for the final boss fight.

DM’s like “here’s the final boss, I gave them a huge number of legendary saves so you can’t just banish them”

Let me tell you, the noise a DnD table makes when you say “uh DM, please don’t roll initiative for the final boss, I’d like them to roll a 1 thank you.” gold.

Could you eli5 this?

Guessing it’s DnD 5e.

The boss has legendary resistances, so it has a set number of times where if it fails a saving throw to avoid a spell or other effect (such as banishment), it can choose to succeed instead. Divination wizards have the portent ability, which allows them to replace a roll by anyone they can see with a prerolled die from earlier in the day. Legendary resistances make this irrelevant for saving throws, since the boss can just pass regardless of the roll, but initiative to determine turn order is not a saving throw so it can’t use legendary resistances.

This is DnD 5e yes.

The “divination wizard” in 5e has a power where at the start of the day, they roll two d20 dice (or at high levels, they roll three d20 dice), then they put them aside for later. At any point during the adventuring day, whenever anyone the wizard can see makes any d20 roll for any reason, the wizard’s player can say “wait stop, don’t roll the dice for that, instead your result is THIS dice” and they use up one of their stored dice. This feature is called “portent” - it represents the wizard seeing the future.

So for example, if you roll a high number (let’s say, a 17) - and an enemy wizard casts a very nasty spell, causing your friend to have to make a saving throw, you can say “this looks scary, and if you fail this check, you’ll die. I’m going to declare that you rolled a 17 for this save.”

Most players when they see this feature think about the high numbers, those are “powerful” feeling because they let you succeed at doing something when it really matters - and this can make a big difference - when the outcome of a story comes down to “can we convince the important NPC we’re the good guys?” one roll can make a huge difference, and getting to make the check knowing what the outcome can be is phenomenally powerful. As players you can even plan to make full use of this - coming up with a plan of action where everything hinges on a single die roll is normally very dangerous in DnD, but when you can force that roll to be good, it’s an incredibly powerful tool.

One thing that many players dont consider, however, is the raw power of a very low roll. You can use these portent dice when enemies make checks, so if you have a small number, you can make an enemy fail. One of the most common uses of this will be to cast a spell that causes a monster to make a saving throw, or suffer serious consequences (e.g. a spell like “polymorph” can turn a monster into a snail for an hour, effectively letting you win the fight against them with a single roll.) - these are commonly referred to as “save or suck” spells, and the big weakness of them is, if the enemy makes the saving throw, nothing happens. You wasted your turn, and used a powerful spell slot and got nothing. These spells get significantly more potent when you have portents.

(Another incredibly powerful use of portent is to use dice in a pair - let’s say you need to lie to the head of the city guard to cover your tracks, or you need to win a contest of strength against a minotaur. If you have both a high and a low die in your portent pool, you can make the contest, and give yourself the high die while giving your opponent the poor die. This lets your tiny puny wizard win a tug of war against a Minotaur, or lie to the guard captain and have him absolutely believe you - and you know in advance what the outcome will be!)

In general, the most powerful monsters in DnD 5e are called “legendary monsters” and they have a special power where - whenever they fail a saving throw, they can say “actually, this is really bad for me, I’m going to treat this like I passed the saving throw” - this means you can’t just defeat the final boss with a single spell, they’re protected against it. Generally these monsters get to do this three times, which means you need to hit them with a “save or suck” effect four times to win the fight, but monsters can have a smaller number, or a larger number of these, depending on their design, and what the dungeon master wants out of the fight.

In this case, our Dungeon Master wanted the final boss to last a long time, and be a big epic affair, so she gave the boss ten legendary saves. (He was a god, after all.) - so she was confident that our group would have to fight him the normal way, and she was right. There was no way for me to use the portent fight to cheaply defeat the final boss in a single spell…

However - initiative - the skill check you make at the start of fights, is a d20 roll as well… so you can use the portent dice to change that outcome. When a whole group of people is fighting one very dangerous boss in DnD, “initiative” becomes one of the most important rolls in the game. The monster gets relatively few turns, but they’re very impactful. The difference between them rolling high and going early vs rolling low and going late is massive - using the portent die to make the final boss act last effectively served as a free turn for the entire party. This is just as powerful as many “save or suck” effects.

Our group had played through a full campaign of monsters, seeing my wizard use this one tool to mess with enemies for the entire time, so by the time we reached the end of the campaign, over a year after we started, they were all pretty used to seeing it have a big impact on the game - however, knowing what we were fighting, they were expecting it to be a fairly minimal impact there. High numbers would be helpful, but they’d be forcing one roll to be a success in a fight that needed ~50 successes to beat. The boss could use legendary saves on most spells, so the low numbers wouldn’t be helpful at all. So everyone was surprised to see the lowest die roll have probably the greatest impact of any die roll in the entire campaign.

This is really cute!

I get that a lot.

That first one reminded me of a story I heard at a small SF convention in LA back in the '90s.

This writer was working on The Real Ghostbusters (long story behind that name) and in the episode they go in the space shuttle to a space station. Everyone on the space station is a Star Trek character analog and so hilarity ensues as the rest of the episode is just a Star Trek spoof.

One of the characters is based on Janice Rand who, in the show, had a basket-weave hairdo. The writer included in the script a note to the animators about her hair. The animators were Asian and did not know what a basket-weave was, and it being pre-Wikipedia, they just made an assumption. The test animation they got back had the Janice Rand-alike with a basket literally woven into her hair.

They kept it in the final episode, of course.

Edit: found it, at about 2:30 https://www.crackle.com/watch/d4228840-874e-418c-afd7-a9b93146e6ed/the-real-ghostbusters/ain’t-nasa-sarily-so

Can’t open it outside of the US. Could you maybe post a screenshot?

How did the first tin cans get opened? A chisel and a hammer, writes Kaleigh Rogers for Motherboard. Given that the first can opener famously wasn’t invented for about fifty years after cans went into production, people must have gotten good at the method. But there are reasons the can opener took a while to show up.

Our story starts in 1795, when Napoleon Bonaparte offered a significant prize “for anyone who invented a preservation method that would allow his army’s food to remain unspoiled during its long journey to the troops’ stomachs,” writes Today I Found Out. (In France at the time, it was common to offer financial prizes to encourage scientific innovation–like the one that led to the first true-blue paint.) A scientist named Nicolas Appert cleaned up on the prize in the early 1800s, but his process used glass jars with lids rather than tin cans.

“Later that year,” writes Today I Found Out, “an inventor, Peter Durand, received a patent from King George III for the world’s first can made of iron and tin.” But early cans were more of a niche item: they were produced at a rate of about six per hour, rising to sixty per hour in the 1840s. As they began to penetrate the regular market, can openers finally started to look like a good idea.

But the first cans were just too thick to be opened in that fashion. They were made of wrought iron (like fences) and lined with tin, writes Connecticut History, and they could be as thick as 3/16 of an inch. A hammer and chisel wasn’t just the informal method of opening these cans–it was the manufacturer’s suggested method.

The first can opener was actually an American invention, patented by Ezra J. Warner on January 5, 1858. At this time, writes Connecticut History, “iron cans were just starting to be replaced by thinner steel cans.”

Warner’s can opener was a blade that cut into the can lid with a guard to prevent it from puncturing the can. A user sort of sawed their way around the can’s edge, leaving a jagged rim of raw metal as they went. “Though never a big hit with the public, Warner’s can opener served the U.S. Army during the Civil War and found a home in many grocery stores,” writes Connecticut History, “where clerks would open cans for customers to take home.”

Attempts at improvement followed, and by 1870, the basis of the modern can opener had been invented. William Lyman’s patent was the first to use a rotary cutter to cut around the can, although in other aspects it doesn’t look like the modern one. “The classic toothed-wheel crank design” that we know and use today came around in the 1920s, writes Rogers. That invention, by Charles Arthur Bunker, remains the can opener standard to this day.>