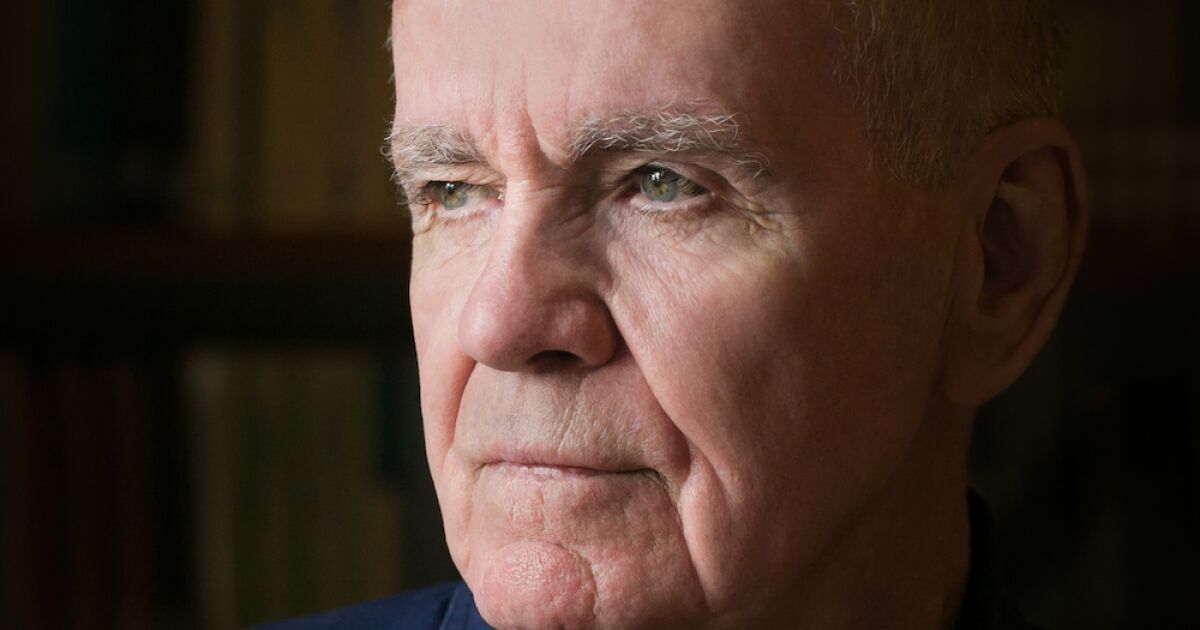

For the entirety of my writing life, Cormac McCarthy has been a mountain. Some of the novelists of my generation found the mountain beautiful; others found it oppressive. But virtually all of us, whatever our position or attitude, existed in its shade.

In spite of the enormity of his shadow, however, I’ve never before written about the author of so many novels I’ve studied and admired. In the two decades since my first book was published, I’ve fielded the boilerplate question about my influences no end of times, name-checking an almost absurdly ragtag crew: Shirley Hazzard, Denis Johnson, William S. Burroughs, Amos Tutuola, Lydia Davis, Toni Morrison, John Berger, Ursula K. Le Guin — even, just a few weeks ago, whoever ghost-wrote David Lee Roth’s memoir, “Crazy From the Heat.” But one name I’ve conspicuously avoided all these years has been that of McCarthy, who died last week at 89. Why on earth is that?

From the first paragraph — from the first sentence — “All the Pretty Horses” reconfigured my understanding of novelistic language so radically that months would pass before I felt able to read anyone else. All these years later, its opening still hits me with the force of incantation: The candleflame and the image of the candleflame caught in the pierglass twisted and righted when he entered the hall and again when he shut the door. Book cover for “All the Pretty Horses” by Cormac McCarthy, featuring a black-and-white image of a horse’s mane.

(Knopf)

That line has lost none of its mystery, its austerity, its elegant foreboding. Part of what makes it so memorable, of course, is its odd, self-consciously archaic cadence — the oft-cited ‘biblical’ loftiness of McCarthy’s prose, which may be one reason few writers of my generation care to cite him as an influence. But although I registered the novel’s considerable stylistic debts both to Hemingway and Faulkner — not to mention “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” — I was so intoxicated by its music that the point seemed academic. It didn’t matter that McCarthy’s literary models were obvious, because he wrote as well as they did and occasionally better. For a would-be novelist struggling under my own debilitating anxiety of influence, no more valuable lesson existed. I received it as a physical sensation. I could breathe.

But something even more powerful was at work as I read, something harder to make sense of, let alone characterize: At the time I thought of it — always in italics — as the sound. Intuitively, on the margins of my consciousness, I came to understand: The sound was the thing. It set the mood, it lit the world, it kept everything in motion. This second lesson was, if possible, even more pivotal than the first: Never mind your plot outline, your carefully thought-out themes, your take on human nature. Forget your own name if you have to. It may take years, it may be agony — but find the sound. That’s all you need. The rest of it will follow.

The news of McCarthy’s death — somehow surprising, even startling, in spite of his age — is the reason, of course, for this belated mea culpa. I can’t help but think, looking back, that certain younger writers, myself included, resisted acknowledging McCarthy’s influence not because of what he was, necessarily, but because of what he represented — and whatever our conception of him now, he has also, with his passing, come to represent the past.

But this was true, curiously enough, even during the long years of McCarthy’s prime. Vital as his best work always was to me as a point of reference, the man himself, and how he (purportedly) lived — his Olympian detachment, his monkish day-to-day existence, his refusal to give interviews or readings or to besmirch himself in any of the myriad ways demanded of working writers nowadays — always seemed an impossible act to follow. A man with a beard wearing black clothes in front of a brick wall with graffiti.

John Wray was in a rough place when he picked up Cormac McCarthy’s “All the Pretty Horses.” It set fire to his writing and changed his life.

(Julio Arellano)

Until the runaway success of “Horses,” when McCarthy was 59, none of his novels had sold more than a few thousand copies, and he gave every impression of finding obscurity pleasant. At times his very existence, out there somewhere, banging contentedly away on his Olivetti Lettera, could feel … daunting, I suppose. He regularly refused lucrative speaking engagements, teaching positions, and — needless to say — any social media presence whatsoever. What young writer could get away with that today? Perhaps more to the point, would any of them want to?

For this reason and others, McCarthy’s passing feels to me — as I’m sure it does to many — like the closing of a long and momentous chapter in American letters. He was, de facto, the last of the great Harold Bloom-anointed White Cisgender Male Authors, and no small number of critics and academics, I suspect, are now quietly wishing that era Godspeed.

White cisgender male though I am, far be it from me to disagree: I’ve never felt the awe and adoration for Bellow and Mailer and Irving that seemed mandatory among well-read middle-class readers of my parents’ generation, and I’ve always been slightly nauseated by Updike’s randiness and verbal exhibitionism. McCarthy, however, though he was born in the same year as Philip Roth, was never a member of that particular gentlemen’s club. I imagine he must have struck a writer like Updike as a walking anachronism, a coelacanth-like living fossil from the high modernist age. And in fact — occasionally for the worse, but very, very often for the better — that’s exactly what he was.

None of which is to say that McCarthy’s body of work, or even his worldview, has subsided into irrelevance with his death — just the opposite. I was recently asked by a music magazine to write a list of “novels for metalheads,” and my thoughts went instantly to “Blood Meridian,” his end-of-days magnum opus of the American West. The conjunction of metal and McCarthy isn’t as far-fetched as it might seem; in its pitch-black reckoning with humanity’s most self-annihilating urges, the novel could easily be read as an allegory for the Anthropocene. The apocalyptic orange skies that recently darkened the East Coast might have been conjured directly from its dread-filled pages.

I had a dog-eared copy of “Blood Meridian” beside me when I wrote the following passage in my most recent novel, in which a teenage boy hears heavy music for the first time: “He was being offered the same purifying fear, the same catharsis, the same revelation midnight slasher movies gave: that everything wasn’t going to be all right. Not now and not ever. And that made perfect sense to him.”