- cross-posted to:

- hackernews@lemmy.smeargle.fans

- cross-posted to:

- hackernews@lemmy.smeargle.fans

There is a discussion on Hacker News, but feel free to comment here as well.

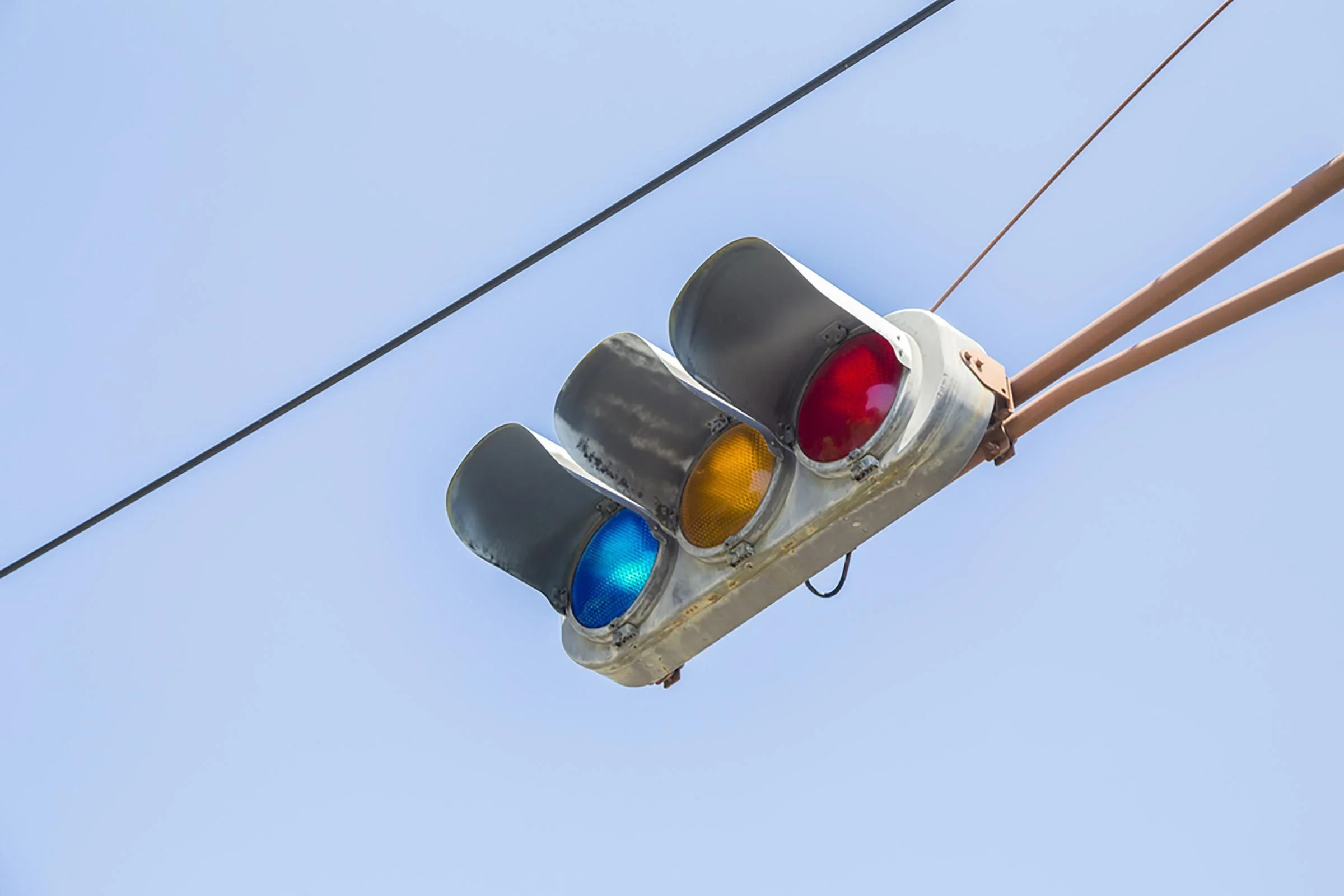

This is what happens when you have one word for two colors.

Not quite. The number of colours itself is language-dependent. Easier shown with an example:

The three gems in the pic are emerald, turquoisite and lapis respectively. How many colours are there?- Japanese (old style) - “one: they’re all different shades of 青 ao”

- English - “two: the emerald is green and the other two are blue”

- Russian - “three: they’re зелёный zeljonyj, голубой goluboj, and синий sinij respectively”

From Russian PoV, English is the one using “one word for two colours”, and Japanese used one for three.

…or at least that’s how Japanese did it. The primary colours of a language can change over time - splitting, migrating, or even merging (in rare situations). And that’s exactly what happened with Japanese, with 緑 midori changing meaning from “verdure” to “a hue of 青 ao”, and then telling the later “GET OFF MY LAWN, I’M NOW A PRIMARY COLOUR!”.

For reference, English did the same around the XVI century, with a shade of yellow (more specifically yellow-red). It’s now called “orange”.

I mean, you really should have words for at least 6 distinct colours, those being red, yellow, blue, green, orange and purple.

Additional words for stuff like brown may be left out, but those six colours should be named.

you really should have words for at least 6 distinct colours, those being red, yellow, blue, green, orange and purple.

Even if those six were the actual primary and secondary colours, it wouldn’t be necessary to have a primary word for each. You can refer them by hue, or by referring to some object.

Also, note that the “true” colour wheel (based on our light reception) is more like red, yellow, green, cyan, blue and magenta. (No orange; and purple is kind of far from magenta.) The wheel that you’re implying by those six colours is mostly an artistic “distortion” of the 18th century. And yet it isn’t cross-linguistically common to take cyan or magenta as “named” colours, they’re often seen as hues of blue/green and red/rose/purple respectively.

(Some societies live just fine with three colours - “dark”, “light”, and “red”.)

Even if those six were the actual primary and secondary colours, it wouldn’t be necessary to have a primary word for each. You can refer them by hue, or by referring to some object.

But you don’t - that’s why languages lacking these words run into issues as described in the article.

The wheel that you’re implying by those six colours is mostly an artistic “distortion” of the 18th century.

But isn’t there a good reason it was distorted that way?

Of course some colours take up much more or much less of the visible colour spectrum, but that doesn’t mean they have more significance to us.

Like red taking up over five times more of the colour spectrum than yellow doesn’t mean that all these reds need to be named. Most red tones are hardly distinguishable to most people. Yellow and red on the other hand can be distinguished with ease.

You won’t run into the issue of differently coloured traffic lights in english countries; because while the traffic lights might use slightly different shades of green, they don’t use drastically different colours - because we properly named them.

But you don’t [refer to them by hue]

People do it fairly often. Specially when precision is needed. Vermilion red, ultramarine blue, so goes on.

that’s why languages lacking these words run into issues as described in the article.

The issue is not lacking a word, but mismatching usage - in this case, between Japanese as used by the speakers versus the legislation. It wouldn’t happen if the speakers kept using 青/ao for emerald-coloured stuff - they’d look at the emerald-coloured go light, say “it’s ao!”, legislation agrees, all is well.

And it is certainly not directly the result of a lack of words for those six arbitrarily specific tones, as this example shows:

The soil in the picture is called “terra roxa” in Portuguese. It means “purple soil” (red soil would be “terra vermelha”). It’s the exact same underlying issue as in Japanese - you call it by one name, and yet the underlying colour is another.And, while there are potential three reasons why it might be called this way (old Spanish explorers, Portuguese internal change, Italian colonists), all of them involve some mapping mismatch:

English Spanish Italian Portuguese, old usage Portuguese, modern usage red rojo rosso roxo vermelho purple púrpura porpora púrpura roxo And yet in no relevant moment the language lacked a distinction between red and purple. On the contrary - it has three words for that range. (“Púrpura” is nowadays mostly a fancy synonymous for “roxo”, but based on Galician usage odds are that all three were distinct at some point; for reference modern Hungarian does it too).

But isn’t there a good reason it was distorted that way?

That’s mostly appeal to ignorance - “we don’t know, so it’s caused by this”.

That distorted colour wheel is likely the result of the access to pigments and traditional usage back then, and lack of access to knowledge on how our eyes process light.

Also note two things:

- before synthetic dyes there was little practical use for a specific word for blue.

- the biggest distinction, the one that you see across all languages out there, is missing from those six colours. It’s “dark” vs. “light”.

You won’t run into the issue of differently coloured traffic lights in english countries

A “country” speaks no language. That is not just nitpicking - the issue is a mismatch between the language as used by the population vs. the legislation.

And yes, this issue could happen if English remapped the colour used to refer to green, through some semantic shift.

You just made me realise i dont know what indigo is

It’s a plant.

I’ll comment this separately because it refers to a Hacker News comment, and it’s a bit of off-topic:

Differences are quite common with colour terms - you don’t need to go to Japanese (blue-green) or Ancient Greek (wine dark sea) for this.

While the comment that this excerpt comes from is mostly accurate, including the core claim, the Greek example is not.

This myth that Ancient Greek considered the sea “wine-coloured” comes from people lacking poetic sensibility misinterpreting excerpts of the Illiad and the Odyssey, where Homer uses the expression οἶνοψ πόντος / oînops póntos “wine-eyed sea”. Like this one:

- [Original] νῦν δ᾽ ὧδε ξὺν νηὶ κατήλυθον ἠδ᾽ ἑτάροισιν // πλέων ἐπὶ οἴνοπα πόντον ἐπ᾽ ἀλλοθρόους ἀνθρώπους,

- [1919 English translation] And now have I put in here, as thou seest, with ship and crew, while sailing over the wine-dark sea [SIC - poor translation IMO] to men of strange speech

“Wine-eyed” does not refer to the colour. Homer is calling the sea a drunkard - it’s violent, erratic, whimsy, drowsy. Mentes (actually Athena) in this excerpt is highlighting the difficulties of his travels, that involve dealing with barbarians and with a violent sea.

The same applies to other excerpts.